- Home

- Dan Wright

The CIA UFO Papers Page 2

The CIA UFO Papers Read online

Page 2

Long years later, in a seemingly innocuous interoffice note, came an unexpected acknowledgment that UFO-related research was still ongoing at the Agency. Scientists were collecting sighting reports, accumulating evidence, and correlating findings. Like an interminable itch, the Central Intelligence Agency necessarily kept on scratching—and may well still be doing so to this day.

These files released to the CIA website in 2017 do not constitute a tell-all file dump—though Agency officials might protest that assertion. To demonstrate, each chapter (most comprising a single year) concludes with a section titled “While you were away from your desk...” There, UFO incidents of consequence in that same year, arising in the United States or elsewhere, are summarized. These are cases that were not mentioned in the 2017 cache of documents. A majority of these involved pilots, police, and other trained observers. As officially stated concerning the US Air Force and its Project Blue Book, events potentially involving a national security threat were withheld. One could expect nothing different from the CIA. The 550 or so usable files on the Agency's website are, as a certain president under threat of impeachment once said, a “limited hangout.” Still, in sum they tell quite a story.

Chapter 1

The 1940s: War and Beyond

In July 1940, Franklin Roosevelt appointed a new Secretary of the Navy, Frank Knox. Months later, Knox introduced him to William “Wild Bill” Donovan, a much-decorated World War I commander. Two decades after that pinnacle, Donovan was a successful New York lawyer. He would ultimately be the only person in American history to receive every one of our highest service awards: Medal of Honor, Distinguished Service Medal, and National Security Medal. He also earned a Silver Star, Purple Heart, and decorations from numerous nations for his World War I service. But his efforts in the next war made an even greater difference. At CIA Headquarters, Bill Donovan was and is the Father of American Intelligence.1

Donovan conceived of an agency that would combine the gathering of sensitive information with propaganda and subversion. Roosevelt was impressed with his ideas on intelligence and its place in modern war. In the summer of 1941 FDR decided to force the military and civilian services to cooperate on intelligence matters. He tapped Donovan to lead the mission as the White House's Coordinator of Information.2

Donovan initially divided his staff into separate analysis and propaganda wings. In short order, the military branches, chafing at being assigned espionage roles during peacetime, persuaded Roosevelt to hand their respective undercover units to Donovan.3

Along with those staff acquisitions, Donovan was given access to unvouchered cash from the President's emergency fund (appropriated by Congress to be spent under personal responsibility of the President or a designated White House official). The expenditures were not audited in detail; Donovan's signature on a note attesting to their proper use sufficed.4

Donovan and his staff recruited, in particular, Americans outside government circles who studied world affairs, frequently traveled abroad, or both—some of the best and the brightest at East Coast universities, businesses, and law firms. These recruits brought the practices and disciplines of their academic and professional backgrounds. Making use of their efforts, he reasoned, would forge answers to many intelligence problems. Those solutions would be found in libraries, contemporary journalism, and the filing cabinets of business and industry.5

Following Pearl Harbor and America's entry into the Second World War in 1942's initial months, Roosevelt endorsed the military's idea of moving Donovan and his recruits under the control of the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS). But FDR wanted to keep a newly formed Foreign Information Service, a radio broadcasting arm, out of military hands.

Though military pressure on the White House had resulted in Donovan reporting to the Joint Chiefs, an undercurrent of resistance within the ranks remained for a time. At issue was that the long-since civilian Donovan was on a par with the individual commanding generals and admirals. But those misgivings were eventually quelled and nothing came of the discontent.

Just as Americans were settling into the slog of what was becoming a long war, unusual sights commenced inexplicably in the months to follow. Dutch sailors on the Timor Sea near New Guinea were on the lookout for enemy aircraft on February 26, 1942, when a large luminous disc approached at great speed. For hours it flew in broad circles around the ship at moderate speed and altitude. Contrasting that peaceful event was one occurring a month later on March 25. An RAF bomber returning from a mission to Essen, Germany, was over Holland's Zeider Zee when the tail gunner noticed a luminous disc or sphere approaching. After notifying the pilot, the gunner readied his weapon and waited. When it was within 100–200 yards, he fired several rounds, apparently hitting it, but to no effect. Shortly the vehicle flew away at a speed that the crew thought to be beyond the speed of sound.6

Early successes of British commandos prompted Roosevelt to authorize, in June 1942, the evolution of the Coordinator of Information into a full-scale intelligence service—modeled after Britain's MI6. Renamed the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), it would likewise be under the command of General Donovan. This was to be a military/intelligence meeting of the minds. Donovan's staff now totaled 600, spending ten million dollars per year.7

The agency's name change may have implied a move toward a darker side of data collection. It fulfilled Donovan's wish for an office name reflecting the clandestine importance of the work. The OSS mandate was to collect and analyze strategic information—anything of potential assistance to the war effort. This was America's first organized attempt to implement a centralized system for secret military intelligence.

Nicknamed the “Glorious Amateurs,” OSS even employed once and future celebrities, including Hollywood actress Marlene Dietrich and later TV chef Julia Child, as well as four future CIA directors. At its peak, the OSS was deploying over 13,000 operatives (that is, spies), a third of them women.8 Their daring missions into Austria and Germany, especially, were essential to turning the tide for the Allies.

Contrasting those clandestine efforts was a massive, open display in the Pacific Theater on August 12, 1942. As told by an observer, a GI on combat duty on Tulagi, one of the Solomon Islands, heard an air raid siren and leaped into his foxhole, rifle at the ready, expecting an attack by Japanese warplanes. Instead he was amazed to see overhead a swarm of unknowns, which he estimated at about 150, in a series of straight-line formations, passing by high in the sky. He did not know their purpose or where they were headed. All he knew was that they were definitely not Japanese zeroes.9

When World War II reached its dramatic climax at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, resulting in Japan's quick surrender, OSS remained in service to the military but needed to be repurposed. On September 20, 1945, a Truman executive order dissolved the agency only to re-form it a few months later, out of necessity. OSS, in a reduced role, would remain part of the intelligence establishment until after the Korean Conflict.10

The first public mention of a “central intelligence gathering agency” appeared on a White House command-restructuring proposal to a congressional military affairs committee at the end of 1945. Despite resistance from the military, Department of State, and FBI, by executive order, Truman formed a National Intelligence Authority—the direct predecessor of the CIA—in January 1946. Its operational extension was known as the Central Intelligence Group (CIG).11

On July 26, 1947, Truman affixed his signature to the National Security Act of 1947, which dissolved the CIG and established both the National Security Council and the Central Intelligence Agency.12

A primary impetus for the CIA's creation—the desire to continue espionage efforts beyond the renewal of peace—lay in the retrospective shock of the December 1941 Pearl Harbor attack amidst diplomatic negotiations with Japanese authorities. Ears to the ground, it was reasoned, might have anticipated that attack and prepared for it.

The Agency (insiders' simplified handle) was originally housed on Navy Hill in Washington, D.C. It

s stated purpose was to create a clearinghouse for foreign policy and analysis. Essentially, it would collect, evaluate, and disseminate foreign intelligence reports, while performing covert actions as necessary.13

Nazi UFOs?

While common knowledge has tagged the origin of saucer reports to the summer of 1947, a latent CIA internal document dialed back that date to Germany's World War II effort. In August 1953, an operative somewhere in Europe completed and distributed a by-then standard Agency reporting form, Information from Foreign Documents or Radio Broadcasts (IFDRB). The operative's source claimed personal knowledge that, as early as 1941, a large cadre of German scientists and engineers drew up preliminary plans for an unconventional flying craft.14

That effort was led in part by a brilliant 29-year-old aerospace engineer, Wernher von Braun. At the Breslau, Germany, complex, he was charged with creating a flying vehicle unlike any other: unconventional in appearance and propulsion. By 1944, the source continued, three if not more of the experimental vehicles had been fashioned. It is unclear from the record what became of the plans or whether the crafts were ultimately destroyed.

Nazi saucer experiments were not confined to the Breslau complex. Using tens of thousands of ethnic prisoners as slave laborers, an enormous tunnel-connected circuit of underground complexes was dug in southwest Poland. Dubbed Project Lothar—apparently for a hero in medieval German folklore—the engineering effort there intended to create a bell-shaped object, approximately three meters in diameter, either electrical or nuclear powered, with vertical takeoff ability. Later, Igor Witkowski, a Polish journalist and military historian, wrote extensively about the bell in his book, Prawda O Wunderwaffe (Reality of the Wonder Weapon), published in 2000.15

Nazi Georg Klein later publicly supported Witkowski's claim that such design efforts had been undertaken. The aeronautical engineer remarked, “I don't consider myself a crackpot or eccentric or someone given to fantasies.... This is what I saw with my own eyes, a Nazi UFO.”16

Former CIA agent Virgil Armstrong stated that before World War II's conclusion, the SS possessed at least two fully formed Haunebu flying saucers (presumably named for the proving grounds where the prototypes were designed, in Hauneburg, Germany). One was capable of speeds up to 1,200 mph, plus 90-degree turns and vertical takeoffs and landings, he claimed. Armstrong said other crafts were capable of twice that speed.

On the 15th of August, 1945, President Harry Truman issued an executive order concerning what to do with a cache of German materials relating to the study of new technologies. An attendant covert operation known as Paperclip began in March 1946. It was, in reality, the vehicle to spirit German scientists into the United States for the purpose of developing “miracle weapons systems.” The assembled group was headed by Wernher Von Braun.17 A German-produced televised documentary in 2014, UFOs in the Third Reich, speculated that the Roswell, New Mexico, incident in July 1947 was linked to testing of the bell. The producers stated that the craft was the forerunner of stealth technology, crafted by Von Braun and scores of V2 rocket experts. Paperclip was fulfilling its goal of affording the United States an edge over the Soviet Union in rocket and other advanced technologies.18

Before and After Roswell

On August 1, 1946, an Army Air Force captain in the Tactical Air Command was piloting a C-47 cargo plane from Langley Field, Virginia, to MacDill Field, Tampa, Florida. Just northeast of Tampa, flying at 4,000 feet, the pilot, copilot, and flight engineer observed what looked like an incoming meteor. At 1,000 yards, the object turned sideways and crossed the airplane's path. They realized it was twice the size of a B-29 bomber and cylindrical with luminous portholes. A stream of fire issued from the rear. The anomaly—America's very own ghost rocket, so often reported in Sweden and throughout Scandinavia that year—was in view for three minutes.

Six weeks before the Roswell incident, May 19, 1947, at Manitou Springs, Colorado, seven railroad workers were eating lunch outside when they caught sight of a silvery, flat-bottom object, ovular in shape. It stopped overhead then moved “erratically in wide circles” 1,000 feet above. After 20 minutes the ship flew away in a straight line until out of sight.19

On June 24, 1947, the so-called modern age of UFOs began with a 3:00 p.m. sighting by Kenneth Arnold, a civilian pilot. As he was flying near Washington state's Cascade Mountain range, searching for a downed C-46 military transport plane, he saw nine identical, gleaming aerial objects. Thin in profile, they flew in a chain-like formation, bobbing and weaving through the mountain passes. Using two known peaks as guides, Arnold estimated their speed as over 1,200 mph. His homily to a reporter afterward that the objects “flew like a saucer would if you skipped it across the water” gave rise to the term flying saucer. The Army Air Corps dismissed the sighting as a mirage.20

An internal FBI memorandum dated July 10, 1947, titled “Flying Discs,” outlined an official request by Army Air Corps General George Schulgren. The general requested the Bureau's help with a recent spate of aerial saucer reports. When obtained later, the memo included a handwritten note at the bottom by FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover. The note read, “I would do it but before agreeing to it we must insist upon full access to discs recovered. For instance in the La. case the Army grabbed it & would not let us have it for cursory examination.”21

For those who overlooked the August 1, 1946 anomaly observed by a military pilot in Florida (see page 6) or the broader Scandinavian ghost rocket phenomena that year, a replication in the United States took place in the predawn hours of July 25, 1948, in the skies of Alabama. The pilot and copilot of an Eastern Airlines DC-3 confronted an oncoming unknown.

“It flashed down toward us and we veered to the left,” said the captain later. Streaking by some 700 feet to their right, it zoomed up into the clouds and was gone. The pilots described it as a wingless aircraft about 100 feet long without any protruding surfaces. Along its side, stretching the entire length of the fuselage, was a medium-dark blue glow. What appeared to be portals were seen along its length. Investigators from the newly minted United States Air Force determined that a C-47 transport was the only aircraft in the vicinity, and it did not report any such incident.22

Soon agencies similar to the young Central Intelligence Agency, patterned after Britain's successful MI6, would find their way into the governments of Australia, France, Russia, China, India, Pakistan, Egypt, and Israel. The fundamental purpose of each was to warn/inform leaders of important overseas events.

The CIA's Executive Office within the Department of Defense (DoD) provided the US military with information it gathered, received data from military intelligence agencies, and cooperated on field activities. To guard against counterespionage, CIA employees would undergo periodic polygraph exams.

At its birth—just three weeks removed from the famed incident outside Roswell, New Mexico—no one involved in organizing this new agency, international in scope, could have imagined it would eventually be dragged into the quagmire of unidentified flying objects (UFOs), known colloquially back then as flying saucers.

In the months immediately following Roswell, saucer reports rather suddenly started flooding newspaper offices nationwide, many from otherwise credible witnesses who had heard little or nothing about Roswell. These would be buttressed by periodic magazine features speculating on what the unusual machines might represent.

One such event that received little or no press attention, but may have made its way to the Agency, occurred at Muroc Army Air Field, California, which by then was on high alert, with fighter aircraft fueled and perched on a runway. A few days after Roswell, at 9:20 a.m., July 8, 1947, a lieutenant and three other servicemen at Muroc observed two spherical objects over the base, flying at an estimated 300 mph. Earlier that morning, two Army engineers at the same base reported two metallic discs “diving and oscillating” overhead. Whether discretion was the better part of valor or just out of fear, no interceptor was ordered up to investigate.23

The still-situatin

g CIA leadership likely did not know how, if at all, to respond to all the UFO hullabaloo. Flying saucers were a domestic matter, after all, beyond the reach of the Agency's formal charter. Then again, the Muroc incident did originate with the military, the Agency's close ally.

On September 23, 1947, General Nathan Twining, later Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, wrote a letter to the Commanding General of the Army Air Forces, entitled “Flying Discs”:

The phenomenon reported is something real and not visionary or fictitious.... The reported operating characteristics such as extreme rates of climb, maneuverability (particularly in roll), and action which must be considered evasive when sighted or contacted by friendly aircraft and radar, lend belief to the possibility that some of the objects are controlled either manually, automatically, or remotely.24

In a heated September 27, 1947, letter to Air Force General George MacDonald, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover terminated the Bureau's initial cooperation on UFO matters. In his letter, Hoover paraphrased a September 3, 1947, letter from Air Defense Command Headquarters that described the FBI's role. Hoover said he was not interested in “relieving the Air Force of running down incidents which in many cases turned out to be ‘ash can covers, toilet seats, and whatnot.’” Four days later an FBI bulletin to its field offices formally ended the joint investigations.25

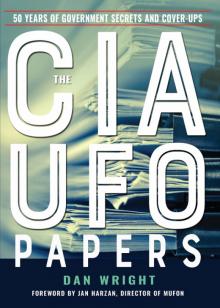

The CIA UFO Papers

The CIA UFO Papers